One Ring to Rule Them All Funny

| The One Ring | |

|---|---|

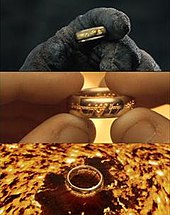

Artist'due south representation | |

| Get-go appearance | The Hobbit (1937) |

| Created by | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| In-story information | |

| Type | Magical ring |

| Function | Invisibility Ability augmentation Volition domination Control over other Rings of Ability |

| Specific traits and abilities | Plain gold ring; glowing inscription appears when ring is placed in flames; can change in size by its own will |

The One Ring, besides called the Ruling Ring and Isildur'south Bane, is a central plot chemical element in J. R. R. Tolkien'due south The Lord of the Rings (1954–55). It get-go appeared in the earlier story The Hobbit (1937) as a magic ring that grants the wearer invisibility. Tolkien inverse it into a malevolent Ring of Ability and re-wrote parts of The Hobbit to fit in with the expanded narrative. The Lord of the Rings describes the hobbit Frodo Baggins's quest to destroy the Ring.

Critics have compared the story with the band-based plot of Richard Wagner'due south opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen; Tolkien denied whatsoever connectedness, but at the least, both men drew on the same mythology. Another source is Tolkien's analysis of Nodens, an obscure pagan god with a temple at Lydney Park, where he studied the Latin inscriptions, ane containing a expletive on the thief of a ring.

Tolkien rejected the idea that the story was an allegory, saying that applicability to situations such as the Second World War and the atomic bomb was a matter for readers. Other parallels accept been drawn with the Band of Gyges in Plato's Commonwealth, which conferred invisibility, though there is no proffer that Tolkien borrowed from the story.

Fictional description [edit]

Purpose [edit]

The 1 Ring was forged by the Dark Lord Sauron during the Second Age to proceeds dominion over the free peoples of Eye-earth. In disguise every bit Annatar, or "Lord of Gifts", he aided the Elven smiths of Eregion and their leader Celebrimbor in the making of the Rings of Ability. He so forged the 1 Ring in the fires of Mount Doom.[T one]

Sauron intended it to be the most powerful of all Rings, able to rule and control those who wore the others. Since the other Rings were powerful on their own, Sauron was obliged to place much of his own ability into the I to reach his purpose.[T two]

Creating the Band simultaneously strengthened and weakened Sauron. With the Ring, he could control the power of all the other Rings, and thus he was significantly more powerful after its creation than before;[T iii] but by binding his ability within the Ring, Sauron became dependent on it.[T 1] [T 3]

Advent [edit]

The Band seemed to be made simply of gold, but information technology was completely impervious to damage, even to dragon fire (unlike other rings).[T i] It could be destroyed only by throwing it into the pit of the volcanic Mount Doom where it had been forged. Like some lesser rings, but unlike the other Rings of Power, it bore no precious stone. It could alter size, and mayhap its weight, and could of a sudden expand to escape from its wearer.[T 1] Its identity could exist adamant past placing it in a fire, when information technology displayed a fiery inscription in the Black Spoken communication that Sauron had devised. This was written in the Elvish Tengwar script, with ii lines in the Black Speech from the rhyme of lore describing the Rings:[T 4]

| Blackness Speech written in Tengwar | Black Spoken communication (Romanised) | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| Ash nazg durbatulûk, ash nazg gimbatul, Ash nazg thrakatulûk agh burzum-ishi krimpatul. | Ane ring to rule them all, ane ring to find them, One ring to bring them all and in the darkness demark them. |

When Isildur cut the Ring from Sauron's manus, it was burning hot, its inscription legible; he transcribed it earlier it faded. Gandalf learned of the Ring's inscription from Isildur's account, and heated Frodo'southward ring to display the inscription, proving that this was the One Ring. Gandalf recited the inscription ( ![]() Pronunciation ) in Black Speech at the Council of Elrond, causing everyone to tremble:[T 5]

Pronunciation ) in Black Speech at the Council of Elrond, causing everyone to tremble:[T 5]

The alter in the wizard's voice was astounding. Suddenly it became menacing, powerful, harsh equally stone. A shadow seemed to laissez passer over the high sun, and the porch for a moment grew dark. All trembled, and the Elves stopped their ears.[T five]

Internal history [edit]

Later on forging the ring, Sauron waged war on the Elves. He destroyed Eregion and killed Celebrimbor, the maker of the iii Elf-rings. Rex Tar-Minastir of Númenor sent a neat fleet to Middle-world, and with this aid Gil-galad destroyed Sauron'south regular army and forced Sauron to return to Mordor.[T two]

Subsequently, Ar-Pharazôn, the last and near powerful male monarch of Númenor, landed at Umbar with an immense regular army, forcing Sauron's armies to flee. Sauron was taken to Númenor as a prisoner.[T 6] Tolkien wrote in a 1958 letter that the surrender was both "voluntary and cunning" so he could gain access to Númenor.[T 7] Sauron used the Númenóreans' fearfulness of expiry to plow them against the Valar, and manipulate them into worshipping his master, Morgoth, with man sacrifice.[T six]

Sauron's body was destroyed in the Fall of Númenor, but his spirit travelled back to Middle-world and wielded the One Ring in renewed war against the Last Alliance of Elves and Men.[T 6] Tolkien wrote, "I practice not call up one need boggle at this spirit conveying off the Ane Ring, upon which his power of dominating minds now largely depended."[T 7]

Gil-galad and Elendil destroyed Sauron's concrete form at the end of the Last Alliance, at the price of their ain lives. Elendil's son, Isildur, cut the Ring from Sauron'south hand on the slopes of Mount Doom. Though counselled to destroy the Ring, he was swayed past its ability and kept it "as weregild for my father, and my brother". A few years later, Isildur was ambushed by Orcs by the River Anduin near the Gladden Fields; he put on the Ring to escape, but it chose to sideslip from his finger every bit he swam, and, suddenly visible, he was killed by the Orcs. Since the Ring indirectly caused Isildur'south death, it was known in Gondorian lore as "Isildur'due south Bane".[T 2]

The Ring remained hidden on the river bed for almost 2 and a half millennia, until it was discovered on a angling trip by a Stoor hobbit named Déagol. His friend and relative Sméagol, who had gone fishing with him, was immediately ensnared by the Band'south ability and demanded that Déagol give it to him as a "birthday present"; when Déagol refused, Sméagol strangled him and took the Ring. It corrupted his body and mind, turning him into the monstrous Gollum. The Band manipulated Gollum into hiding in a cave under the Misty Mountains well-nigh Mirkwood, where Sauron was beginning to resurface. There Gollum remained for virtually 500 years, using the Ring to hunt Orcs. The Ring eventually abandoned Gollum, knowing information technology would never leave the cave whilst he bore it.[T one]

As told in The Hobbit, Bilbo found the Ring while lost in the tunnels near Gollum'due south lair. In the first edition, Gollum offers to surrender the Ring to Bilbo equally a advantage for winning the Riddle Game. When Tolkien was writing The Lord of the Rings, he realized that the Band's grip on Gollum would never permit him to give it up willingly. He therefore revised The Hobbit: in the second edition, afterward losing the Riddle Game to Bilbo, Gollum went to get his "Precious" to help him impale and eat Bilbo, but found the Ring missing.[1] Deducing from Bilbo'south terminal question—"What have I got in my pocket?"—that Bilbo had found the Band, Gollum chased him through the caves, non realizing that Bilbo had discovered the Ring'due south power of invisibility and was following him to the cave'south mouth. Bilbo escaped Gollum and the goblins by remaining invisible, but he chose not to tell Gandalf and the dwarves that the Ring had fabricated him invisible. Instead he told them a story that followed the first edition: that Gollum had given him the Ring and shown him the fashion out. Gandalf was immediately suspicious of the Band, and later forced the real story from Bilbo.[T 1] [T viii] [T nine]

Gollum eventually left the Misty Mountains to track downwardly the Ring. He was drawn to Mordor, where he was captured. Sauron tortured and interrogated him, learning that the Ring had been institute and was held past one "Baggins" in the land of "Shire".[T one]

The Ring began to strain Bilbo, leaving him feeling "stretched-out and thin", then he decided to leave the Shire, intending to pass the Ring to his adopted heir Frodo Baggins. He briefly gave in to the Band'south power, even calling it "my precious"; alarmed, Gandalf spoke harshly to his quondam friend to persuade him to requite it upwards, which Bilbo did, becoming the first Band-bearer to give up it willingly.[T 10]

By this time Sauron had regained much of his power, and the Dark Tower in Mordor had been rebuilt. Gollum, released from Mordor, was captured by Aragorn. Gandalf learned from Gollum that Sauron now knew where to observe the Ring.[T 11] To prevent Sauron from reclaiming his Ring, Frodo and viii other companions set out from Rivendell for Mordor to destroy the Ring in the fires of Mount Doom.[T 12] During the quest, Frodo gradually fell nether the Ring's ability. When he and his faithful servant Sam Gamgee discovered Gollum on their trail and "tamed" him into guiding them to Mordor, Frodo began to experience a bond with the wretched, treacherous creature, while Gollum warmed to Frodo'south kindness and fabricated an try to go on his promise.[T thirteen] Gollum however gave in to the Band's temptation, and betrayed Frodo to the spider Shelob.[T fourteen] Believing Frodo to be dead, Sam bore the Band himself for a short time and experienced the temptation it induced.[T fifteen]

Sam rescued Frodo from Orcs at the Tower of Cirith Ungol.[T sixteen] The hobbits, followed by Gollum, reached Mountain Doom, where Frodo was overcome by the Ring's power and claimed it for himself. At that moment, Gollum bit off his finger, taking dorsum the Ring, but, gloating, he and the Ring fell into the fires of Mount Doom. The Ring and Sauron's power were destroyed.[T 17]

Powers [edit]

The Ring's primary power was control of the other Rings of Power and domination of the wills of their users.[T iii] The Band also conferred power to dominate the wills of other beings whether they were wearing Rings or not—simply only in proportion to the user's native capacity. In the aforementioned way, it amplified any inherent power its owner possessed.[T three]

A mortal .. who keeps one of the Great Rings, does not dice, but he does not abound or obtain more life, he merely continues, until at last every infinitesimal is a weariness. And if he often uses the Ring to make himself invisible, he fades: he becomes in the stop invisible permanently, and walks in the twilight under the eye of the nighttime power that rules the Rings.

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring [T one]

A mortal wearing the Ring became effectively invisible except to those able to perceive the non-physical world, with but a thin, shaky shadow discernible in the brightest sunlight.[T three] All the same, when Sam wore the band on the edge of Mordor, "he did not experience invisible at all, but horribly and uniquely visible; and he knew that somewhere an Centre was searching for him".[T 15] Sam was able to sympathize the Blackness Speech of Orcs in Mordor during his brief possession of the One Ring.[T 18]

The Ring extended the life of a mortal possessor indefinitely, preventing natural aging. Gandalf explained that it did not grant new life, just that the owner merely continued until life became unbearably wearisome.[T 1] The Band did not protect its bearer from devastation; Gollum perished in the Cleft of Doom,[T 19] and Sauron'due south body was destroyed in the downfall of Númenor. Like the Nine Rings, the 1 Ring physically corrupted mortals who wore it, eventually transforming them into wraiths. Hobbits were more resistant to this than Men: Gollum, who possessed the ring for 500 years, did not become wraith-similar considering he rarely wore the Ring.[T 1] Except for Tom Bombadil, nobody seemed to be immune to the corrupting effects of the One Band, even powerful beings like Gandalf and Galadriel, who refused to wield it out of the noesis that they would become like Sauron himself.[T 5]

Within the land of Mordor where it was forged, the Band'southward power increased then significantly that even without wearing it the bearer could depict upon it, and could acquire an aura of terrible power. When Sam encountered an Orc in the Belfry of Cirith Ungol while holding the Band, he appeared to the terrified Orc as a powerful warrior cloaked in shadow "[holding] some nameless menace of power and doom".[T 16] Similarly at Mount Doom, when Frodo and Sam were attacked by Gollum, Frodo grabbed the Ring and appeared as "a figure robed in white... [that] held a wheel of burn". Frodo told Gollum "in a commanding phonation" that "If yous impact me e'er again, you shall be bandage yourself into the Burn of Doom", a prophecy presently fulfilled.[T 17]

As the Band contained much of Sauron'south ability, it was endowed with a malevolent agency. While separated from Sauron, the Ring strove to return to him by manipulating its bearer to claim ownership of it, or by abandoning its bearer.[T 20]

To master the Ring's capabilities, a Band bearer would need a well-trained mind, a strong will, and peachy native power. Those with weaker minds, such every bit hobbits and bottom Men, would gain piddling from the Band, permit lone realize its full potential. Fifty-fifty for one with the necessary strength, it would have taken time to chief the Ring'due south power sufficiently to overthrow Sauron.[T twenty]

The Ring did not render its bearer omnipotent. Three times Sauron suffered war machine defeat while bearing the Ring, first by Gil-galad in the State of war of Sauron and the Elves, and so by Ar-Pharazôn when Númenórean power and so overawed his armies that they deserted him, and at the end of the Second Age with his personal defeat by Gil-galad and Elendil.[T two] Tolkien indicates in a speech by Elrond that such a defeat would not have been possible in the waning years of the Tertiary Age, when the strength of the gratuitous peoples was greatly macerated. There were no remaining heroes of the stature of Gil-galad, Elendil, or Isildur; the strength of the Elves was fading and they were parting to the Blessed Realm; and the Númenórean kingdoms had either declined or been destroyed, and had few allies.[T v]

Fate of the Ring-bearers [edit]

Of the Ring-bearers, 3 were live after the Ring's destruction, the hobbits Bilbo, Frodo, and Sam. Bilbo, having borne the Ring the longest, had his life much prolonged. Frodo was scarred physically and mentally by his quest. Sam, having only briefly kept the Ring, was affected the least. In consideration of the trials Bilbo and Frodo faced, the Valar allowed them to travel to the Undying Lands, accompanying Galadriel, Elrond, and Gandalf. Sam is as well said to have been taken to the Undying Lands, after living in the Shire for many years and raising a big family unit. Tolkien emphasized that the restorative sojourn of the Ring-bearers in the Undying Lands would not take been permanent. Every bit mortals, they would somewhen die and exit the earth of Eä.[T 20]

Assay [edit]

Norse mythology and Wagner [edit]

Tolkien's use of the Band was influenced by Norse mythology. While at King Edward's School in Birmingham, he read and translated from the Old Norse in his costless fourth dimension. One of his first Norse purchases was the Völsunga saga. While a student, he read the only bachelor English translation,[2] [3] the 1870 rendering by William Morris of the Victorian Arts and Crafts motion and Icelandic scholar Eiríkur Magnússon.[iv] That saga and the Eye High German Nibelungenlied were coeval texts that used the same ancient sources.[five] [half-dozen] Both of them provided some of the basis for Richard Wagner's opera serial, Der Band des Nibelungen, featuring in particular a magical but cursed golden ring and a cleaved sword reforged. In the Völsunga saga, these items are respectively Andvaranaut and Gram, and they correspond broadly to the I Ring and the sword Narsil (reforged every bit Andúril).[7]

Tolkien dismissed critics' direct comparisons to Wagner, telling his publisher, "Both rings were circular, and there the resemblance ceases."[T 21] [T 22] Some critics hold that Tolkien's work borrows and so liberally from Wagner that it exists in the shadow of Wagner's.[8] Others, such every bit Gloriana St. Clair, aspect the resemblances to the fact that Tolkien and Wagner had created works based on the same sources in Norse mythology.[9] [viii] Tom Shippey and other researchers hold an intermediary position, stating that the authors indeed used the same source materials, but that Tolkien was indebted to some of the original developments, insights and artistic uses of those sources that get-go appeared in Wagner, and sought to improve upon them.[10] [11] [12]

Nodens [edit]

Tolkien visited the temple of Nodens at a identify called "Dwarf's Hill" and translated an inscription with a curse upon the thief of a ring. It may have inspired his dwarves, mines, rings, and Celebrimbor "Silver-Mitt", the Elven-smith who forged Rings of Power.[13]

In 1928, a quaternary-century heathen mystery cult temple was excavated at Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.[14] Tolkien was asked to investigate a Latin inscription there, which mentioned the theft of a band, with a curse upon its thief:

For the god Nodens. Silvianus has lost a ring and has donated one-half [its worth] to Nodens. Among those who are called Senicianus do not permit wellness until he brings information technology to the temple of Nodens.[xv]

The Anglo-Saxon name for the place was Dwarf'southward Hill, and in 1932 Tolkien traced Nodens to the Irish gaelic hero Nuada Airgetlám, "Nuada of the Silverish-Paw".[T 23] Shippey idea this "a pivotal influence" on Tolkien's Middle-earth, combining every bit it did a god-hero, a band, dwarves, and a silver mitt.[13] The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia notes the "Hobbit-like appearance of [Dwarf's Colina]'south mine-shaft holes", and that Tolkien was extremely interested in the hill'south sociology on his stay there; it cites Helen Armstrong's comment that the place may have inspired Tolkien's "Celebrimbor and the fallen realms of Moria and Eregion".[13] [xvi] The scholar of English literature John G. Bowers writes that the name of the Elven-smith Celebrimbor, who forged the Elf-rings, is the Sindarin for "Silver Manus".[17]

Applicability non allegory [edit]

Tolkien stated that The Lord of the Rings was not a betoken-by-bespeak apologue, particularly not of political events of his time such as the Second World War.[T 24] At the aforementioned time he assorted "applicability", which he described as "inside the "freedom of the reader", and "allegory" as "the purposed domination of the author".[T 24] He stated that had the 2nd World War "inspired or directed the development of the legend" as an allegory, then the fate of the Ring, and of Heart-earth, would take been very different:[T 24]

| Story element | Lord of the Rings | Allegory in Foreword |

|---|---|---|

| The Band | Destroyed | Seized, used against Sauron |

| Sauron | Annihilated | Enslaved |

| Barad-dur | Destroyed | Occupied |

| Saruman | Fails to get the Band, is killed | Goes to Mordor; in the confusion and treachery learns to make his own Ring, makes war on the new Ruler of Centre-world |

| Issue | Peace, the Shire restored | War, hobbits enslaved and destroyed |

Anne C. Petty, writing in The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, notes that Tolkien was still quite capable of using "allegorical elements when it suited his purpose", and that he agreed that the approach of war in 1938 "had had some effect on information technology": Lord of the Rings was applicable to the horror of war in general, as long as it was not taken as a bespeak-by-point allegory of any item war, with faux equations like "Sauron=Satan or Hitler or Stalin, Gandalf=God or Churchill, Aragorn=Christ or MacArthur, the Ring=the atomic bomb, Mordor=Hell or Russia or Frg".[18]

One aspect of such applicability, that the Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey notes is rarely picked up by readers, is that Tolkien chose dates of symbolic importance in Christianity for the quest to destroy the Ring. Information technology began in Rivendell on 25 December, the date of Christmas, and ended on Mount Doom on 25 March, a traditional Anglo-Saxon date for the crucifixion.[nineteen]

Parallels with Plato's Republic [edit]

A source that Tolkien "might accept borrowed"[20] from, though there is no evidence for this, is Plato's Commonwealth. Its second book tells the story of the Ring of Gyges that gave its owner the power of invisibility. In so doing, information technology created a moral dilemma, enabling people to commit injustices without fearing they would exist caught.[20] In contrast, Tolkien'due south Ring actively exerts an evil force that destroys the morality of the wearer.[T 25]

The scholar of humanities Frederick A. de Armas notes parallels between Plato'southward and Tolkien'southward rings, and suggests that both Bilbo and Gyges, going into deep dark places to find hidden treasure, may have "undergone a Catabasis", a psychological journey to the Underworld.[21]

| Story element | Plato's Commonwealth | Tolkien'southward Middle-globe |

|---|---|---|

| Ring's power | Invisibility | Invisibility, and corruption of the wearer |

| Discovery | Gyges finds ring in a deep chasm | Bilbo finds band in a deep cave |

| First use | Gyges ravishes the Queen, kills the Rex, becomes Male monarch of Lydia | Bilbo puts band on "by accident", is surprised Gollum does not come across him |

| Moral result | Full failure | Bilbo emerges strengthened |

The Tolkien scholar Eric Katz, without suggesting that Tolkien was aware of the Ring of Gyges, writes that "Plato argues that such [moral] corruption will occur, but Tolkien shows us this corruption through the thoughts and actions of his characters".[22] In Katz'south view, Plato tries to counter the "contemptuous decision" that moral life is chosen by the weak; Glaucon thinks that people are but "good" considering they suppose they will be caught if they are non. Plato argues that immoral life is no good as it corrupts one'due south soul. So, Katz states, according to Plato a moral person has peace and happiness, and would not employ a Band of Power.[22] In Katz's view, Tolkien's story "demonstrate[south] diverse responses to the question posed by Plato: would a but person exist corrupted past the possibility of almost unlimited ability?"[22] The question is answered in unlike means: Gollum is weak, quickly corrupted, and finally destroyed; Boromir begins virtuous but like Plato's Gyges is corrupted "by the temptation of power"[22] from the Ring, even if he wants to use it for expert, but redeems himself past defending the hobbits to his ain death; the "stiff and virtuous"[22] Galadriel, who sees clearly what she would become if she accustomed the ring, and rejects it; the immortal Tom Bombadil, exempt from the Band's corrupting power and from its gift of invisibility; Sam who in a moment of need faithfully uses the ring, but is not seduced by its vision of "Samwise the Strong, Hero of the Historic period"; and finally Frodo who is gradually corrupted, simply is saved by his earlier mercy to Gollum, and Gollum's desperation for the Band. Katz concludes that Tolkien's answer to Plato's "Why exist moral?" is "to exist yourself".[22]

Object of the quest [edit]

The scholar of the humanities Brian Rosebury noted that The Lord of the Rings combines a slow, descriptive series of scenes or tableaux illustrating Centre-earth with a unifying plotline in the shape of the quest to destroy the Ring. The Ring needs to be destroyed to salvage Center-earth itself from destruction or domination by Sauron. The work builds upwards Middle-earth as a place that readers come to love, shows that it is nether dire threat, and – with the devastation of the Band – provides the "eucatastrophe" for a happy ending. The work is thus, Rosebury asserted, very tightly constructed, the expansive descriptions and the Ring-based plot fitting together exactly.[23]

Addiction to power [edit]

The Ring offers power to its wearer, and progressively corrupts the wearer'due south heed to evil.[24] [25] The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey applies Lord Acton's 1887 argument that "Power tends to decadent, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men" to it. He notes that the opinion is distinctively modernistic, and that other modern authors such as George Orwell with Creature Farm (1945), William Golding with Lord of the Flies (1954), and T. H. White with The Once and Future King (1958) similarly wrote about the corrupting effects of power. When the critic Colin Manlove described Tolkien'due south attitude to power every bit inconsistent, arguing that the supposedly overwhelming Ring was handed over easily enough by Sam and Bilbo, and had little outcome on Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli, Shippey replies in "ane word" that the caption is simple: the Ring is addictive, increasing in effect with exposure.[26] Other scholars agree well-nigh its addictive nature.[24] [25] [27] [28]

Adaptations [edit]

In the 1981 BBC Radio series of The Lord of the Rings, the Nazgûl dirge the Ring-inscription; the BBC Radiophonic Workshop's audio effects for the Nazgul and the Black Speech of Mordor take been described as "nightmarish".[29] [30]

In Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, the wearer of the Ring is portrayed as moving through a shadowy realm where everything is distorted. The effects of the Ring on Bilbo and Frodo are obsessions that have been compared with drug addiction; the actor Andy Serkis, who played Gollum, cited drug addiction as an inspiration for his functioning.[31] The actual ring for the films was designed and created by Jens Hansen Gold & Silversmith in Nelson, New Zealand, and was based on a simple wedding ring.[32] [33] Polygon highlighted that "the workshop produced approximately 40 unlike rings for the films. Nigh expensive were the 18 carat solid gilded 'hero' rings, sized 10 for Frodo'south paw and 11 for the chain. [...] To save money — though not fourth dimension — the workshop used aureate-plated sterling silver for about of the rings. [...] For many fans, the band used in close-ups — like the scene where the Ring slips abroad from Frodo to lure Boromir in the snow at Caradhras, or when arguing participants in the Council of Elrond are shown reflected in the Ring'southward surface — is the existent hero band. In lodge to capture the ring's sheen in high definition, that prop was a full 8 inches wide — as well big fifty-fifty for Hansen's tools. Instead, a local machine store made and polished the shape that Hansen'due south team and so plated".[33]

A tabletop roleplaying game prepare in Middle-earth and called "The One Ring" was manufactured by Cubicle seven;[34] a new edition is planned by a partnership of Sophisticated Games and Free League Publishing from 2020.[35] [36]

References [edit]

Primary [edit]

-

- This listing identifies each detail's location in Tolkien'south writings.

- ^ a b c d e f grand h i j The Fellowship of the Band, book ane, ch. 2 "The Shadow of the Past"

- ^ a b c d The Silmarillion, "Of the Rings of Ability and the Third Age"

- ^ a b c d e Carpenter 1981, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

- ^ A drawing of the inscription and a translation provided by Gandalf appears in The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 2 "The Shadow of the Past".

- ^ a b c d The Fellowship of the Band, book 2, ch. ii, "The Council of Elrond"

- ^ a b c The Silmarillion, "Akallabêth"

- ^ a b Carpenter 1981, #211 to Rhona Beare, fourteen October 1958

- ^ The Hobbit, ch. 5 "Riddles in the Dark"

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, Prologue "Of the Finding of the Band"

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 1 "A Long-expected Party"

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, volume two, ch. 2 "The Council of Elrond"

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, book two, ch. 3 "The Ring goes South"

- ^ The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 1 "The Taming of Sméagol"

- ^ The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 9 "Shelob'southward Lair"

- ^ a b The Two Towers, volume four, ch. 10 "The Choices of Chief Samwise"

- ^ a b The Render of the King, book half-dozen, ch. one "The Tower of Cirith Ungol"

- ^ a b The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 3 "Mount Doom"

- ^ Tolkien (1954), book iv, ch. x "The Choices of Main Samwise"

- ^ The Return of the King, volume vi, ch. four, "The Field of Cormallen"

- ^ a b c Carpenter 1981, #246 to Mrs Eileen Elgar, September 1963 drafts

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #229 to Allen & Unwin, 23 February 1961

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 206

- ^ J. R. R. Tolkien, "The Proper noun Nodens", Appendix to "Report on the excavation of the prehistoric, Roman and post-Roman site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire", Reports of the Research Commission of the Society of Antiquaries of London, 1932; as well in Tolkien Studies: An Annual Scholarly Review, Vol. 4, 2007

- ^ a b c d The Fellowship of the Ring, "Foreword to the 2d Edition"

- ^ Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Band, volume ane, ch two, "The Shadow of the Past".

Secondary [edit]

- ^ Hammond & Scull 2005, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Byock 1990, p. 31

- ^ Carpenter 1977, pp. 71–73, 77

- ^ Morris, William; Magnússon, Eiríkur, eds. (1870). Völsunga Saga: The Story of the Volsungs and Niblungs, with Certain Songs from the Elder Edda. London: F. S. Ellis. p. xi.

- ^ Evans, Jonathan. "The Dragon Lore of Middle-earth: Tolkien and Sometime English and Quondam Norse Tradition". In Clark & Timmons 2000, pp. 24, 25

- ^ Simek 2005, pp. 163–165

- ^ Simek 2005, pp. 165, 173

- ^ a b Ross, Alex (22 December 2003). "The Band and the Rings: Wagner vs Tolkien". The New Yorker.

- ^ St. Clair, Gloriana (2000). Tolkien's Cauldron: Northern Literature and The Lord of the Rings . Carnegie Mellon University. OCLC 53923141.

- ^ Shippey, Tom (1992). The Road to Middle-globe. Allen & Unwin. p. 296. ISBN978-0-261-10275-0.

- ^ Wickham-Crowley, Kelley Thou. (2008). "Roots and Branches: Selected Papers on Tolkien (review)". Tolkien Studies. 5 (one): 233–244. doi:10.1353/tks.0.0021. S2CID 170410627.

- ^ Manni, Franco (8 December 2004). "Roots and Branches: A Book Review". The Valar Guild. Translated by Bishop, Jimmy. Retrieved four November 2020.

- ^ a b c Anger, Don N. (2013) [2007]. "Written report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Postal service-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Cess. Routledge. pp. 563–564. ISBN978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). pp. 40–41. ISBN978-0261102750.

- ^ "RIB 306. Curse upon Senicianus". Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Armstrong, Helen (May 1997). "And Have an Centre to That Dwarf". Amon Hen: The Message of the Tolkien Society (145): thirteen–fourteen.

- ^ Bowers, John M. (2019). Tolkien'southward Lost Chaucer. Oxford University Press. pp. 131–132. ISBN978-0-19-884267-v.

- ^ Piffling, Anne C. (2013) [2007]. "Apologue". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Cess. Routledge. pp. half-dozen–seven. ISBN978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Route to Centre-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. p. 227. ISBN978-0261102750.

- ^ a b Radeska, Tijana (28 February 2018). "The idea of "the Band" existed centuries before Tolkien'south epic saga". The Vintage News.

- ^ a b de Armas, Frederick A. (1994). "Gyges' Band: Invisibility in Plato, Tolkien and Lope de Vega". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. iii (3/4): 120–138. JSTOR 43308203.

- ^ a b c d e f Katz, Eric (2003). Bassham, Gregory (ed.). The Rings of Tolkien and Plato: Lessons in Power, Choice, and Morality. The Lord of the rings and philosophy : i book to rule them all. Open Court. pp. 5–20. ISBN978-0-8126-9545-viii. OCLC 863158193.

- ^ a b Rosebury, Brian (2003) [1992]. Tolkien : A Cultural Miracle. Palgrave. pp. i–iii, 12–13, 25–34, 41, 57. ISBN978-1403-91263-iii.

- ^ a b Perkins, Agnes; Hill, Helen (1975). "The Corruption of Power". In Lobdell, Jared (ed.). A Tolkien Compass. Open Court. pp. 57–68. ISBN978-0875483030.

- ^ a b Roberts, Adam (2006). "The One Ring". In Eaglestone, Robert (ed.). Reading The Lord of the Rings: New Writings on Tolkien'southward Classic. Continuum International Publishing Grouping. p. 63. ISBN9780826484604.

- ^ Shippey 2002, pp. 112–119.

- ^ Sommer, Mark (seven July 2004). "Fond to the Ring". Hollywoodjesus.com – Pop Civilisation From A Spiritual Point of View . Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Yell, David G. (2007). The Drama of Man. Xulon Press. p. 108. ISBN978-1-60266-768-six.

- ^ "Nazgul.wav". 25 October 2009. Archived from the original (WAV) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved xvi May 2012.

- ^ "Audiobook Review: The Lord Of The Rings: The 2 Towers(1981)". The Orkney News. 22 January 2019. Retrieved iv November 2020.

- ^ "Andy Serkis BBC interview". BBC News. 21 March 2003.

- ^ "The Replica Ring or The One Ring". Jens Hansen - Golden & Silversmith. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ a b Murphy, Sara (half-dozen Oct 2021). "The jeweler who forged the One Ring never got to run into information technology". Polygon . Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ "The One Ring 2nd Ed Character Customisation". Cubicle 7. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Costless League Signs Deal to Publish RPGs in Tolkien's Eye-Earth". Free League. ix March 2020. Retrieved v July 2020.

- ^ Jarvis, Matt (x March 2020). "Tales from the Loop studio becomes new publisher for Lord of the Rings RPGs The Ane Band and Adventures in Heart-earth". Dicebreaker . Retrieved four November 2020.

Sources [edit]

- Byock, Jesse L. (1990). The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Ballsy of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. University of California Press. ISBN0-520-06904-eight.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977), J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography, New York: Ballantine Books, ISBN978-0-04-928037-3

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN978-0-395-31555-ii

- Clark, George; Timmons, Daniel, eds. (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien and His Literary Resonances: Views of Middle-Globe . Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN0-313-30845-4.

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2005). The Lord of the Rings: A Reader'southward Companion. HarperCollins. ISBN978-0-00-720907-one.

- Shippey, Tom (2002). J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. ISBN978-0261104013.

- Simek, Rudolf (2005). Mittelerde: Tolkien und die germanische Mythologie [Eye-globe: Tolkien and the Germanic Mythology] (in German). C. H. Brook. ISBN978-3406528378.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). Douglas A. Anderson (ed.). The Annotated Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002). ISBN978-0-618-13470-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Fellowship of the Ring, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, OCLC 9552942

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Two Towers, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, OCLC 1042159111

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955), The Return of the King, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, OCLC 519647821

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN978-0-395-25730-2

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Ring

0 Response to "One Ring to Rule Them All Funny"

Enregistrer un commentaire